The Transect

The rural-to-urban Transect is based on the idea that there is a place for everything in the human habitat. Where elements of the built environment are in their proper place, the whole is greater than the sum of its parts.

How does the Transect work?

Naturalists use the transect concept to describe ecosystems’ characteristics and the transition from one ecosystem to another. Andres Duany has applied this concept to human settlements, and since about 2000, this idea has permeated the thinking of new urbanists. The rural-to-urban Transect is divided into six zones: core (T6), center (T5), general urban (T4), sub-urban (T3), rural (T2), and natural (T1). The remaining category, Special District, applies to parts of the built environment with specialty uses that do not fit into neighborhoods. Examples include power plants, airports, college campuses, and big-box power centers. The Transect helps design and develop what Duany calls “immersive environments”: urban places where the whole is greater than the sum of its parts.

Duany Plater-Zyberk & Company describes the concept thus: “The Transect arranges in good order the elements of urbanism by classifying them from rural to urban. Every urban element finds a place within its continuum. For example, a street is more urban than a road, a curb is more urban than a swale, a brick wall is more urban than a wooden one, and an allee of trees is more urban than a cluster. Even the character of streetlights can be assigned in the Transect according to the fabrication from cast iron (most urban), extruded pipe, or wood posts (most rural).”

Duany notes that every settlement has its own Transect, which can be studied and mastered. Each differs, to a degree, from all other Transects. For example, all downtowns have unique characteristics. Yet all downtowns have commonalities as well. The Transect concept flows from new urbanists’ observation of urban places and a penchant for systematizing those observations. As a result, transect zones form a patchwork across most communities. A common misconception is that the Transect implies a fried egg pattern from the city center to the edge. That’s only the case in small towns and villages, generally.

The Transect is a powerful tool new urbanists can use to analyze and understand urban places — and ultimately to design new settlements that will possess qualities associated with the best old urbanism. Moreover, because Transect zones can be described and defined, they are beginning to form the basis for a new generation of zoning codes responsive to human-scale needs and desires.

According to version 8.0 of the SmartCode & Manual(primary authors Duany, Sandy Sorlien, William Wright), the Transect “is evident in two ways: 1) it exists as place and 2) it evolves. As a place, the six T-zones display more-or-less fixed identifiable characteristics. Yet the evolution of communities over time is the unseen element in urbanism. For example, a hamlet may evolve into a village and then into a town, its T-zones increasing in density and intensity over many years.”

The following section explains the Transect in some detail.

Urban core

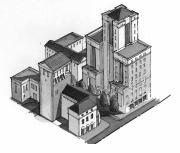

The core (T6) is the densest and most urban part of the human environment. Many cities have only one heart, often known as the downtown, although a large city like New York may have many bodies. “It is the brightest, noisiest, most exciting part of the city,” notes the urban design firm PlaceMakers, in its pattern book for the TND, called The Waters. “… with the city’s tallest buildings, busiest streets, and most variety.”

Many buildings in the core rise above four stories and typically include large office and workplace components. Facilities in the core are highly flexible in their uses — commonly mixing services with shops and businesses on the first floor and offices or residential units above. Most buildings are attached, with their fronts aligned. Complete four-way intersections with rectilinear trajectories (i.e., streets at right angles to each other) are common.

The core is a focal point of activity and energy, benefiting from substantial pedestrian and automotive traffic. Good design allows pedestrians and automobiles to share the streets in a human-scale environment.

Setbacks in the core are generally zero to 10 feet. (Mixed-use buildings with retail on the first floor are built up to the sidewalk.) Sidewalks are broad, typically 6 to 20 feet (the more urban the environment, the wider the sidewalk). Lot sizes vary, from a width of about 18 feet for some townhouses too many times that for a large office or mixed-use building. The percentage of the lot coverage is generally high in the core.

Open space frequently takes the form of plazas. Transit service is the most frequent in the T6 zone. Housing mainly consists of apartments above retail, apartment and condominium buildings, townhouses, and lofts.

In the core, structured parking is the norm. On-street parking is also used widely. Thoroughfares are typically major commercial streets. Net residential densities usually range from 25 to more than 100 units per acre.

Center

The center (T5) is like the core in many ways — buildings typically mix uses, with shops on the first floor and offices and residential units above, and are usually built to the sidewalk — but the character has more of a “main street” feel.

PlaceMakers describes the historical center thus: “The main street neighborhood was as diverse as any, including merchants living over their shops and old folks who didn’t want to have to saddle up to get to all the necessities. You could see lights on in the windows over the square every evening and hear mothers calling their kids to come in and do their homework … .”

Most buildings are attached, with their fronts aligned. Complete four-way intersections with rectilinear trajectories (i.e., streets at right angles to each other) are common. Buildings top out at two to four stories.

Setbacks are short, and sidewalks are wide. Open space often takes the form of squares. Transit is usually available. Housing consists of apartments above retail, stand-alone apartment buildings, townhouses, and live/work units (townhouses designed so that one or more floors can accommodate business activities). Unlike the core, the density allows for surface parking in the center of blocks. Thoroughfares generally consist of main streets and boulevards. Net residential thicknesses typically range from 15 to 40 units/acre.

General Urban

T4, generally urban, is primarily residential but still relatively urban. The streets have sidewalks on both sides, and they have raised curbs. Housing mainly consists of single homes, duplexes, townhouses, and accessory units. Small apartment buildings (up to about eight teams) can be accommodated in the general urban zone if designed to blend in with single homes.

For instance, some businesses may locate in this zone — corner stores and cafes. Churches, schools, and other civic buildings also may appear here. Facilities in the general area are not as large as those in the center. Open space takes the form of parks and greens.

Setbacks generally range from 5 to 25 feet. Many houses have porches, which should be allowed to creep into the setback zone. Lot widths for townhouses range typically from 18 to 30 feet, and for single homes, 30 to 70 feet. Lot lengths generally range from 80 to 130 feet. Rear lanes with garages and accessory units are standard. Ideally, sidewalks should be 5 feet wide to allow two people to walk side by side. Thoroughfares consist primarily of residential streets. Net residential densities in this zone range from 6 to 20 units/acre.

Sub-urban

The sub-urban zone (T3) differs from the conventional suburban development of the past 50 years. Instead, it hews closer to the character of early 20th-century US suburbs. PlaceMakers describes it here: “The sub-urban zone isn’t exactly the ‘burbs. It’s close, to be sure, but it doesn’t include some things like the big box retail you might instead find in a highway business district. Instead, the sub-urban zone is most similar to the areas on the outskirts of town where the town grid begins to give way to nature.”

Although sub-urban is the most residential zone, it can have some mix of uses — examples include civic buildings such as churches, schools, community centers, and occasional stand-alone stores. The lots are more significant, the streets crooked, and the curbs few. Plantings are informal. Setbacks from the road are more important than in the more urban zones, generally ranging from 20 to 40 feet. Porches are plentiful and should be allowed to encroach on the setback. Lot widths usually range from 50 to 80 feet. Lots are often reasonably deep in the sub-urban zone — ranging from 110 to 140 feet — to accommodate an enormous backyard. Lots can range from 5,000 feet to a half acre.

The sub-urban zone accommodates rear lanes, but it is common to find front-loaded houses. (If the home is front-loaded, the garage should still be de-emphasized — set back from the front facade.) Thoroughfares consist primarily of residential streets that have a rural character. Of all the neighborhood areas, density is least in the sub-urban zone, ranging from 2 to 8 units per acre net.

Rural and natural zones

Beyond the neighborhood lie the rural (T2) and natural (T1) zones. The rural zone is the countryside — where development may occur but where it may not be encouraged. “This is the quietest place you can find (except in a thunderstorm or a buffalo stampede), and it’s where the stars shine the brightest,” according to PlaceMakers.

Public infrastructure is sparse or nonexistent in the rural zone. The rural area can be protected from development by transferring rights, land banks, and agricultural zoning.

The natural zone includes parklands, wilderness areas, and areas of high environmental value (such as wetlands) that can withstand court challenges from developers. In addition, it consists of all lands that have been permanently protected from development.

Special Districts

Special Districts (SDs) are urbanized areas specializing in a particular activity. SDs are justified only when their uses cannot be accommodated within the other Transect zones. SDs may contain significant transportation facilities such as airports, truck or bus depots, industrial areas, solid waste disposal and wastewater treatment facilities, hospitals, auto-oriented businesses like auto body shops, or even college campuses. SDs should, like neighborhoods, clearly focus on their physical form. Districts should be interconnected with adjacent areas when possible and prudent to promote pedestrian access. SDs benefit from transit systems.

Although some are pedestrian-friendly (such as college campuses), SDs are the primary means new urbanists employ to accommodate inherently malicious uses. You can’t eliminate services incompatible with human-scale neighborhoods, but you can concentrate on these uses to minimize their damage. You can also place districts adjacent to walkable neighborhoods (if possible), lay them out in a modified grid, build sidewalks, plant street trees, and bring some of the buildings out to the sidewalk. These design elements ensure that, in time, districts can evolve into high-quality urban environments. In the meantime, walking is safe, and the barriers to pedestrian activity are minimized.

Another technique new urbanists use for dealing with pedestrian-hostile activity is the “B” street. Certain auto-oriented activities cannot coexist well with pedestrian activities. Therefore, it’s sometimes best to ensure streets are truly pedestrian-friendly — designated as “A” — and concentrate auto-oriented activities on so-called B streets. Even within a high-quality street network, a B street can accommodate uses such as gas stations, muffler shops, and restaurants with drive-through lanes. A pair of A streets should run parallel to B street on both sides to maintain a walkable environment. B streets can be thought of as districts that are one street wide.

From New Urbanism: Best Practices Guide.

For more information, visit The Center for Applied Transect Studies.